Published by City Farmer, Canada's Office of Urban Agriculture

Red Celery In the Sunshine

An Urban Eden: transforming hopeless backyard hardpan into a lush organic plot

A story about City Farmer's Demonstration Food Garden

Article & photography by Michael Levenston

Originally published in Harrowsmith Magazine

April/May 1984 Number 54

It is little more than a stone's throw from downtown, a means of measure quite appropriate for the volunteers digging, weeding and discarding rocks from the painstakingly created soil that covers the sunny backyard of the Vancouver Energy Information Centre. Here, beautifully illustrated signs identify plants and techniques for gardeners who pass by a cold frame, a large so-lar greenhouse, a three-bin composting system and 30 raised beds filled with healthy vegetables. Occasionally, a train clangs by almost close enough to touch, overwhelming all the other city sounds and reminding the gardeners that not long ago, this little chunk of Eden was not much better suited to growing food than the railway siding next to it.

The garden began to take shape on a warm fall Sunday in 1981, when 11 people met in the backyard of the newly opened centre at Maple Street and Sixth Avenue, overlooking the Burrard Bridge, which spans False Creek and leads to downtown Vancouver. Their spirits high, the volunteers marked the proposed boundaries of the beds and then lunged at the earth with their garden tools like so many horticultural break dancers. After 10 minutes, only one sturdy soul with a pickaxe was left chipping at the cement-like ground. A chemical smell brought the rest of the dejected gardeners to their knees. Was it machine oil, paint thinner or something worse? No one could be sure. Neighbours said that the previous tenants had fixed their trucks in the yard and dumped waste liquids there.

A soil science professor called to the site said that radical surgery was necessary - the present soil had to go. Before any gardening could take place, the top foot of polluted soil would have to be removed and replaced with a commercial topsoil mix. A homeowner faced with a similar problem could build only one bed at a time, digging out a foot-deep rectangle the size of the proposed bed, filling that with purchased topsoil and mounding the soil a further 6 to 12 inches to construct a raised bed. But an urban agricultural project was something special, so the volunteers, whose work was financed by a hodgepodge of provincial, federal and private donations, decided to go to the trouble and expense of replacing all of the soil.

Sponsored by City Farmer (a nonprofit society that was formed in 1978) the Demonstration Food Garden was designed as a place where city people could come and see food growing in a small urban space, and at the same time, they could learn how to grow that food themselves. The would-be city farmers could gain experience by working in the garden under the direction of an experienced food gardener.

URBAN AGRICULTURE

We at City Farmer knew that there was a need for such a facility. We had discovered that 70 percent of Canadians are urban dwellers whose food comes, for the most part, from supermarket shelves. Neither the public education system nor agricultural colleges, which teach large-scale commercial methods of farming, offer courses on small-scale agriculture to urban Canadians who want to learn how to produce some of their food.

The garden serves to demonstrate organic techniques and provides volunteers with a weekly share of fresh vegetables.

In 1982, City Farmer organized a special series of 18 lectures on urban agriculture to introduce Canadians to this new field of study. Subjects as varied as horticulture therapy, rabbit raising and urban air pollution were discussed indoors at the information centre, while outdoors, new topsoil was being spread over what had been an ugly 2,500-square-foot vacant lot. Attending the series of lectures and paying close attention to the work going on outdoors was artist Catherine Shapiro, who is an avid organic gardener with more than 15 years' experience. She was hired as the demonstration garden's head gardener, and under her guidance, the garden began to take shape.

Volunteers double-dug 3-by-11-foot beds to a depth of 2 feet, incorporating some of the original topsoil. Double-digging is a process by which sections of soil are removed, turned and replaced, providing a deeply worked subsoil. The volunteers then raised the beds eight inches above the surface, in the fashion of the Chinese backyard gardens in Vancouver's East End. This combination of double-digging and raised beds, sometimes called the Biodynamic French Intensive Method, works well in rain-soaked Vancouver, because the deep beds leave the raised soil well drained and allow it to warm up quickly in the cool West Coast spring. In general, it is a good technique to use where space is limited, because it adds depth to the garden beds, allowing plants to be planted more closely than usual; roots gain in vertical growing room what they lose in horizontal. At the food garden, we recommend that beginning gardeners start with just one raised bed, then go to four beds be-fore expanding further.

The first four of our beds had been formed by early May 1982, but the crops planted in them did not thrive; it was clear that the beds were not complete. Despite the great efforts of the diggers, the soil was unable to support life adequately because it contained a large proportion of wood chips, a frequent problem with purchased West Coast topsoils. The chips not only stopped moisture from penetrating the surface of the beds but also stole valuable nitrogen from the soil as they slowly decomposed.

Shapiro was not perturbed. Years of organic gardening had shown her that she could make good soil out of any soil. And so, in the months ahead, she spent as much time and care in feeding the earth in the beds as in planting and weeding them. Fifteen cubic yards of rich, black mushroom manure from the prosperous Fraser Valley mushroom industry came to the garden in one large truckload. Comprised of composted horse manure, straw, peat, cottonseed meal and rapeseed meal, it immediately improved the quality of the top foot of soil in each bed, which seemed then like a soup cauldron to which each gardener added the best ingredients to make a perfect meal for the crops that would in turn feed the gardeners. The secret of the garden's suc-cess was the city's hidden organic waste, its horticultural wealth: mushroom manure, garden trimmings, kitchen wastes from a natural-foods restaurant nearby and plastic bags of horse manure brought to the newly built compost bins from stables in the Vancouver Southlands, just 10 minutes away. Occasional soil tests by the B.C. Ministry of Agriculture pointed out the strengths and weaknesses in the soil's fertility.

Shapiro used blood meal and bone meal in 25-pound bags to add nitrogen and phosphorus to the newly formed beds, and dolomite lime was added to sweeten the typically acid soils of Vancouver. "To have a really good garden, you have to go a little bit further than just relying on compost," says Shapiro. "I thought for years that just compost and the occasional load of manure were enough, and I had perfectly adequate gardens, but now, I'm not satisfied with adequate. I want Brassicas that are four feet high and three feet wide."

Volunteers contributed potassium in the form of wood ashes from their homes and seaweed collected on Kitsilano Beach, just down Maple Street.

MARY'S MIX

Fortunately, a store featuring sup-plies for the organic gardener opened its doors not long after the garden got under way. Mary Ballon's Earthrise carried bags of blended fertilizers that proved just right for growing vegetables. Mary's Mix, as the volunteers call the blend, includes canolaseed meal, steamed bone meal, rock phosphate, greensand (a mineral-rich ocean-bottom deposit) and dolomite lime. Gardeners who do not have access to such a mix can purchase individual ingredients in garden stores or by mail order, substituting another meal for canolaseed if necessary.

Each time a crop came out of a bed, the volunteers raked Mary's Mix into the surface area before another crop went in. Each time transplants were moved, Mary's Mix went into the new soil first.

Besides keeping the earth in the beds well tended, Shapiro regularly top-dressed the surface of the soil around the base of the plants with a layer of compost or seaweed. "I don't just top-dress once a month." The third level of soil care came in liquid form. Volunteers served drinks of fish emulsion and manure tea to the plants whenever they showed signs of hunger, such as slowed growth or discoloured foliage.

The Vancouver City Demonstration Garden's volunteers dig fertilizer into deep beds, then raise the beds 8 inches above path level using purchased topsoil.

Throughout the year, seeds were sown, crops were harvested, and the soil was fed, all in a continuous cycle. The attention paid to their nourishment not only helped the plants produce fine vegetables but directly affected their ability to resist pests as well. While blemish-free supermarket cauliflowers grown commercially around B.C.'s Lower Mainland receive an average of 11 sprays of poison from the time they are seeded to the time they are presented to the public in the stores - sprays for diseases, root maggots, aphids, loopers, cutworms, flea beetles, thrips and weeds - no poisons are used in the Demonstration Food Garden, and yet a fine-looking crop of every vegetable is harvested.

The garden's compost pile, is built with manure, vegetable wastes and garden trimmings. Catherine Shapiro displays an organically grown cauliflower.

"The bugs that bother Vancouver gardens are the same from year to year," says Shapiro. "This year, the bugs in the demonstration garden have been minimal because the soil is so good. The best bug prevention is keeping the garden clean, constantly planting and keeping the nutrient level so terrific that no matter what bug comes, your plant is healthy. A plant can survive nearly any kind of bug, provided you've given it optimum conditions. That's the problem, keeping human beings energetic enough to maintain that.

"Unless a bug problem is really bad, I don't pay that much attention to it. I used to think, 'Ooh, bugs,' but I have a friend who was in South America staying with these people who eat caterpillars. The kids take them off the tobacco plants and eat them with delight. That changed my attitude. If you've got a few aphids, and you wash them off, but a few end up in your salad or stir-fry, so what? I just can't understand our obsession with bugs. People whine to me sometimes about bugs, and I just don't want to hear about it, because what's your alternative? It's a poison, isn't it? So I'd rather eat a few bugs."

This is not to say that Shapiro does not use alternative pest-control methods. If she sees a pest problem, she deals with it immediately. For example, when aphids began to appear on some broad beans and on the leaves of the edible chrysanthemums, she and the volunteer gardeners quickly removed all the affected parts of the plants. No further outbreaks damaged the crops.

One crop of spinach, beets and Swiss chard leaves was attacked by leaf-miner maggots, so the next crop was protected with a fine screen that covered the whole bed, preventing the leaf-miner fly from laying its eggs on the leaves. Damage was cut by 95 percent. When cabbage-root maggots invaded tar-paper collars and diatomaceous earth barriers in the cauliflower patch, volunteers top-dressed the injured plants with compost and then fed them teas of garden-grown nettles and comfrey, followed by a second course of fish fertilizer. The plants recovered and produced excellent heads.

Shapiro's techniques for nonpoisonous control of pests vary from insect to insect and from year to year. If she reads about an interesting approach, she puts it to the test. There is more art to her method than science, and she does not like to be pressed for precise measurements: "If I say to somebody that I dip the Brassica roots in lime water, people look at me and say, 'How much lime?' I say I make an insect spray of garlic and chilies. 'How many chilies?' I don't know. I just get a feeling."

By the end of 1983, more than 150 volunteer apprentices had helped develop the garden while improving their own skills - both scientific and intuitive - as urban food gardeners. Some of these individuals were new immigrants who brought with them skills, attitudes and even seeds from their homelands. Others were Canadians on unemployment insurance or welfare who developed a greater sense of self-worth and self-reliance by working in the garden. One beginning gardener simply followed the routine, day by day, in her own garden and thus produced a very successful home garden on her first try. The ways the demonstration garden proved profitable were as numerous and varied as the volunteers and students who came to see it.

Varied, too, were the vegetables that Shapiro grew. She ordered a selection of 150 different kinds of seeds from more than 30 mail-order seed catalogues. Red and purple crops alone dazzled the students in 1983: red Brussels sprouts, purple baby cabbages, red celery, ruby chard, golden beets, red orach (an annual cultivated as a leafy vegetable in France), purple mustard, purple cauliflower and amaranth. The vegetables that surprised most Canadian visitors to the garden were tall, vigorous globe artichokes. Seeds planted in the greenhouse in spring were later transplanted to the garden, producing about 15 large chokes per plant by August.

"I think it would be boring to grow just white cauliflower and green broccoli, "says Shapiro. "Being an artist, I really like to see colour and variety."

Shapiro also planted a wide selection of Chinese and Japanese vegetables, which are well suited to the West Coast climate. Leafy vegetables such as Chinese cabbage, bok choy and mustard greens are "cold-hardy and fast-growing," says Shapiro. 'You plant them continuously and always have something to put in stir-frys and soups. Whenever there's an empty space in the garden, I plant them close together and then eat the trimmings. When I make a salad at home, there are usually 15 or 20 bits of this and that vegetable in it, which is best for our health as well as our taste."

With crops being planted in and harvested from 30 beds year-round, it would be difficult to calculate just how much food is grown in the demonstration garden. However, Shapiro, the garden volunteers and the office workers in the energy centre each took home a weekly share of full bags of garden produce. As the soil in the garden has become richer, the small urban space has become incredibly productive.

The second, third and fourth stages of garden development are now underway. A large solar greenhouse shelters cold-hardy greens during the winter and heat-loving vegetables during the summer. The front and sides of the energy centre are being edibly landscaped with attractive, useful plants such as berry bushes, and finally, the roof of the building will soon support containers of plants, demonstrating rooftop and balcony gardening techniques.

The education programme at the garden will be stepped up in 1984. During every week of Vancouver's 12-month growing season, an organized two-hour class will be held in the garden on a subject appropriate for just that time of year. Classes will no longer be held indoors, with students sitting and teachers lecturing. Students will now have the opportunity to practice bed preparation, fertilization, pest control without poisons, and planting and caring for a wide variety of crops, all under the watchful eye of the garden instructor.

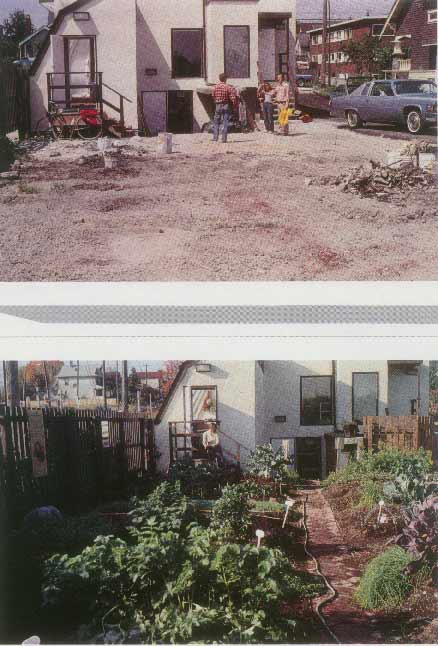

The proposed Kitsilano site of the Vancouver City Demonstration Food Garden was, so the neighbours say, used by the previous tenants as a pit stop and waste dump. Contaminated and with the texture of cement, its soil had to be removed and replaced in order to support abundant crops two years later.

The skills learned by the novice gardeners should be useful in almost any situation. We at City Farmer calculated that Vancouver people could grow all the vegetables they need on land now available within the city limits. Front and back lawns, vacant lots and rights-of-way can average as much as one pound of food per square foot if the gardener uses intensive small-scale agricultural techniques.

It is no wonder, then, that federal government futurists in both Ottawa and Washington are now studying the potential of North American urban agriculture for the coming decades or that international-aid organizations are looking to urban agriculture as a means of helping the burgeoning Third World urban populations feed themselves. They need not look much farther than the corner of Sixth Avenue and Maple Street in Vancouver, where a dedicated group of gardeners and students is proving that a city person with a bit of land exposed to sun and rain can grow some or all of his staple vegetables, and even a little red celery too.

![[new]](new01.gif)